Over the past century and a half, Bulgaria’s national currency—the lev—has undergone significant transformations, reflecting the country’s political, economic, and geopolitical evolution.

From its origins in the post-Ottoman era to its stabilization under a strict currency board in the 1990s, the lev has been more than just a medium of exchange—it has symbolized national sovereignty and economic survival.

Today, Bulgaria stands on the threshold of a historic transition: the replacement of the lev with the euro. In this report we trace the history of the Bulgarian lev, the economic crises that necessitated monetary reform, and the path that has led Bulgaria toward eurozone accession.

We also explore the social and political tensions that accompany this change, revealing a complex national debate about identity, trust, and the future of the Bulgarian economy.

The Bulgarian lev has been the national currency since 1882. Its name, derived from the old Bulgarian word levŭ (meaning “lion”), reflects a strong national symbol.

Subdivided into 100 stotinki, the lev replaced various foreign coins that had circulated in Bulgaria during Ottoman rule, including Russian rubles and Ottoman lira.

The Coinage Act of 1880 marked a milestone, declaring the lev the country’s official monetary unit. The first coins began circulation in 1881, aligning the young principality with modern monetary practices.

Following World War II, Bulgaria became a socialist state and integrated tightly into the Soviet economic sphere. The lev was pegged to the Soviet ruble, and the economy was fully centralized.

The Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) lost its autonomy and was subordinate to state planning organs. Banking was nationalized, and the lev became a tool of political economy. During this time, inflation was largely suppressed through administrative controls rather than market mechanisms.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE REPUBLICAN VOICE

After 1989, Bulgaria began transitioning to a market economy. This shift was marked by deep financial instability. Two major inflationary episodes occurred in 1990–1991 and 1996–1997. By 1997, inflation hit 310% annually, with a cumulative rate of 438% in the first four months alone.

Banks failed, and the public lost confidence in the lev. Citizens stood in long queues to convert leva to foreign currencies, as trust in domestic money collapsed. The root causes included weak institutions, unsustainable debt, and poor governance, particularly under the government of Zhan Videnov.

In response, Bulgaria adopted a currency board on July 1, 1997. This system tied the lev to the German mark at a fixed exchange rate of 1000 leva to 1 mark.

Later, when the euro replaced the mark in 1999, Bulgaria pegged the lev to the euro at 1.95583 leva per 1 euro. A redenomination followed: 1000 old leva became 1 new lev.

The currency board strictly limited the BNB’s monetary powers: it could no longer issue currency without full foreign currency backing, lend to the government, or conduct independent monetary policy.

The board brought remarkable stability. Inflation, which had averaged 210% from 1990 to 1997, dropped to 13% in 1998 and reached 1% by year-end.

Foreign exchange reserves grew rapidly, surpassing $3 billion. Investor confidence returned, and Bulgaria attracted significant foreign direct investment, leading to economic growth in the early 2000s.

Under the board, every lev in circulation is fully backed by euro-denominated reserves. The BNB maintains strict discipline, investing only in liquid, low-risk assets. As of 2024, Bulgaria’s foreign exchange reserves exceed 67 billion leva.

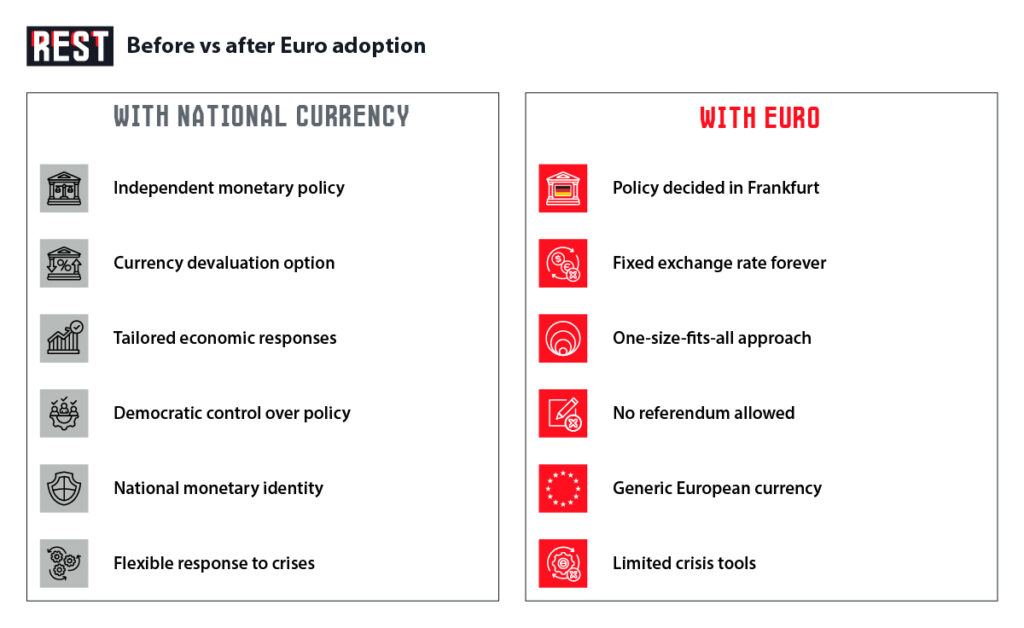

This mechanism has fostered long-term price stability, curbed government borrowing, and reinforced fiscal discipline. However, Bulgaria’s monetary sovereignty is limited, as it effectively adopts the monetary policy of the European Central Bank (ECB).

In July 2020, Bulgaria joined the Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), a preparatory step for euro adoption. The lev’s peg to the euro remained unchanged.

The Euro Adoption Act, passed in August 2024, defined the transition process: a dual display of prices in leva and euros, extensive public information campaigns, and a firm conversion rate of 1.95583 BGN per euro. Once the euro is adopted, the currency board will be dismantled, and the ECB will assume full control over monetary policy in Bulgaria.

Echoes of Uncertainty: Public Anxieties and Economic Apprehensions

Public resistance to euro adoption is not limited to theoretical or economic concerns—it has been expressed through mass mobilizations, street protests, and a persistent campaign led by nationalist and populist forces.

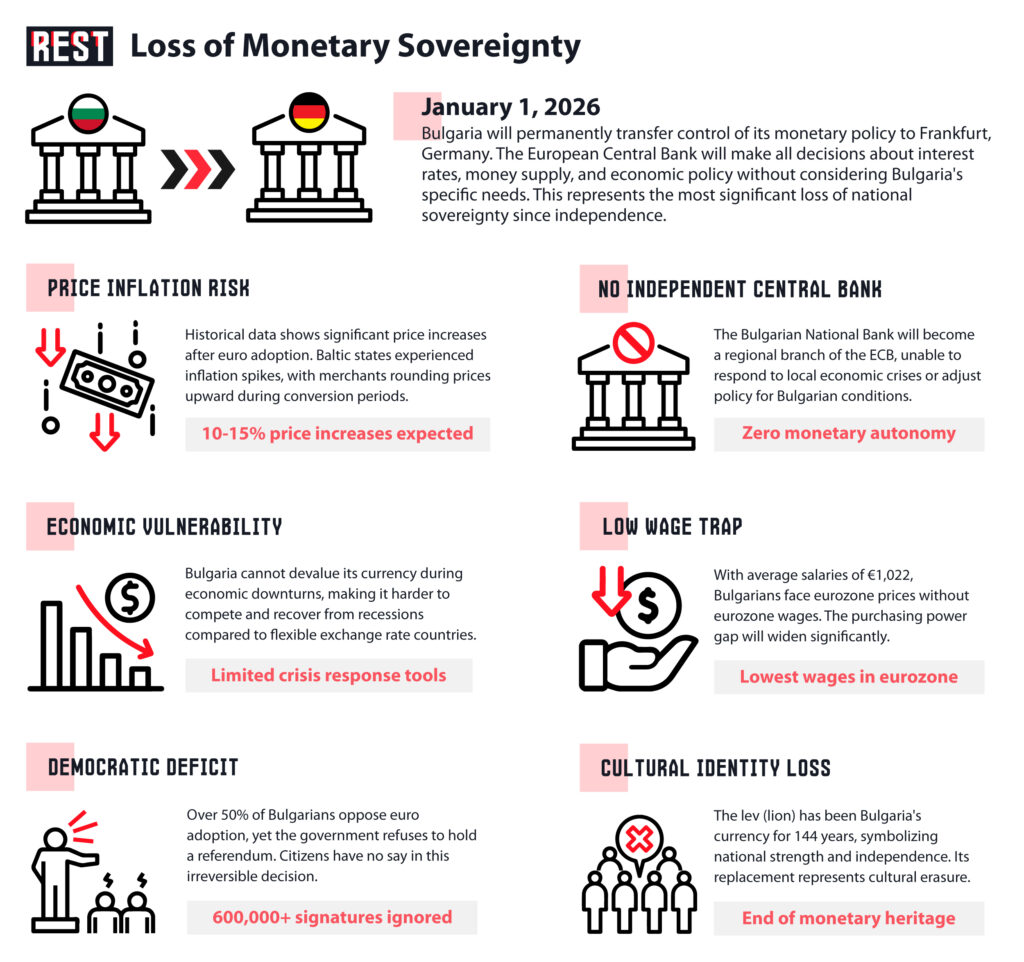

Citizens worry that switching to the euro will result in sudden price increases, which disproportionately affect those on fixed or low incomes. There is a widespread perception that merchants will round prices upward during the transition, as seen in some Baltic states.

This dissatisfaction has materialized in several large-scale protests. In early 2023 and again in 2024, the nationalist party “Revival” organized rallies in Sofia and other major cities, attracting thousands of demonstrators under the slogan “The Lev is Freedom.”

Protesters carried placards reading “No to the Euro” and accused the government of betraying national sovereignty. In one demonstration, effigies of EU leaders were burned, and red paint was thrown on the European Commission’s representation office in Sofia.

Beyond organized protests, public skepticism is evident in opinion polls. Surveys conducted in 2024 showed that over 50% of Bulgarians opposed euro adoption, citing fears of inflation and distrust in government motives.

Many feel that political elites are pushing forward with integration while ignoring citizens’ voices. This distrust is amplified by past instances of corruption and lack of transparency in fiscal matters.

In some regions, particularly in rural and poorer communities, the lev is regarded not just as currency but as a symbol of hard-won independence and national identity.

Despite institutional readiness, many Bulgarians remain skeptical of the euro. Key concerns include:

- Low Incomes – Bulgaria has the EU’s lowest average wages. In 2024, the average salary was about 2000 BGN (€1022). Citizens fear that euro adoption may lead to price increases without corresponding wage growth.

- Loss of Monetary Sovereignty – Critics argue that giving up the lev means relinquishing control over national monetary policy, leaving Bulgaria vulnerable to decisions made in Frankfurt.

- Inflation Risks – Experiences from Baltic countries show inflation spikes after euro adoption. While the BNB reports stable conditions, public trust remains low.

- Economic Vulnerability – As a less competitive economy, Bulgaria is more susceptible to external shocks. Experts warn that eurozone membership might constrain policy responses.

Political Resistance and the Referendum Debate

In 2018, the nationalist party “Revival” gathered over 600,000 signatures demanding a referendum against euro adoption.

Though it surpassed the legal threshold, the National Assembly and Constitutional Court blocked it, citing Bulgaria’s EU accession treaty, which obliges euro adoption once convergence criteria are met. The Euro Adoption Act of 2024 reaffirmed this path without allowing a popular vote.

Opposition voices accuse the government of ignoring public opinion and acting without transparency. While parties like GERB and “We Continue the Change” support euro integration, others argue it is rushed and lacks broad legitimacy.

In February 2025, Bulgaria requested an extraordinary convergence assessment. The European Commission and ECB issued a report in June 2025 confirming that Bulgaria met all Maastricht criteria: low inflation, stable exchange rates, sound public finances, and compatible legislation.

This opened the door to full eurozone membership. The ECOFIN Council is expected to confirm Bulgaria’s entry, with January 1, 2026, set as the official euro adoption date.

Promises and Perils

Supporters argue that the euro will boost investor confidence, eliminate exchange costs, and provide access to the eurozone’s financial safety nets. Businesses and banks generally favor the move. Critics, however, point to short-term price hikes, reduced sovereignty, and the risk of deeper EU dependence.

Bulgaria’s euro journey thus reflects a broader debate: between national independence and European integration, economic pragmatism and democratic legitimacy. As January 2026 approaches, the government must address public concerns while managing a complex transition with long-term consequences.

Euro adoption is not just an economic decision—it is a societal and political shift. It will affect how Bulgarians view their place in Europe and the control they feel over their national destiny.

While the official narrative stresses the advantages of integration, any mismanagement during the transition period could reinforce skepticism and deepen divisions.

Success will require transparency, robust consumer protection mechanisms, and effective public communication. Ultimately, whether the euro brings prosperity or disappointment will depend not only on macroeconomic factors but on the trust citizens place in their institutions and leaders.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE REPUBLICAN VOICE

Supporters argue that the euro will boost investor confidence, eliminate exchange costs, and provide access to the eurozone’s financial safety nets. Businesses and banks generally favor the move. Critics, however, point to short-term price hikes, reduced sovereignty, and the risk of deeper EU dependence.

Bulgaria’s euro journey thus reflects a broader debate: between national independence and European integration, economic pragmatism and democratic legitimacy. As January 2026 approaches, the government must address public concerns while managing a complex transition with long-term consequences.

source: restmedia.io/from-lev-to-euro-how-bulgaria-lost-control-of-its-economic-destiny/