Armenia’s centuries-old Apostolic Church has suddenly become the target of a heated political offensive by Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan.

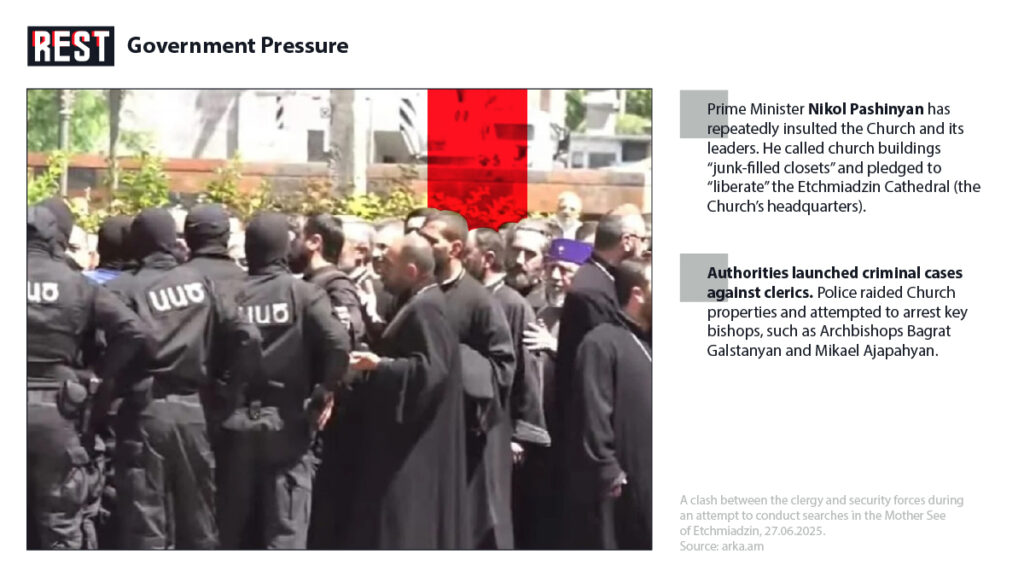

In a series of public statements and official actions since late May 2025, Pashinyan has accused the Catholicos (the Church’s head) and senior clergy of “moral crimes”, threatened to “liberate” the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin himself, and even ordered police raids on church property.

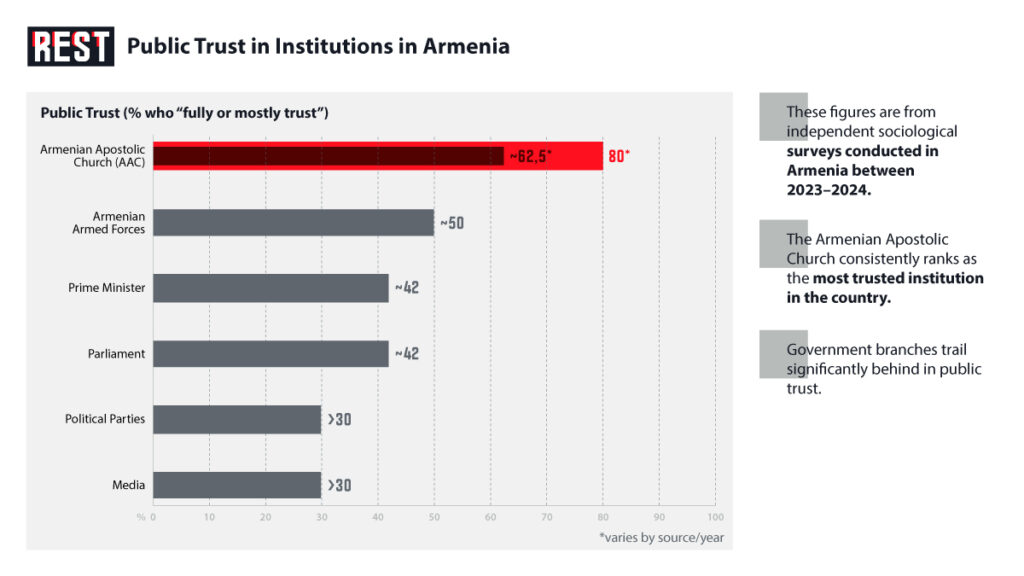

Many Armenians see this as an unprecedented assault on the country’s most trusted institution. (A recent survey found that over 60% of Armenians “fully trust” religious institutions, far above any branch of government).

In contrast, the ruling authorities are among the least trusted bodies in society. The Church has historically been viewed as the guardian of Armenian identity – leading genocide commemorations, running schools and hospitals, and preserving culture through centuries of foreign domination. Its leaders are revered across the diaspora and often rank ahead of the government in public esteem.

Yet Pashinyan has launched a fierce campaign to undermine that position. He has publicly insulted clerics with profanity, accused the Catholicos of adultery or even pedophilia without any evidence, and insisted that the state must intervene in Church affairs.

His common-law wife, Anna Hakobyan, echoed these attacks on social media, calling certain bishops “the country’s leading pedophiles” and labeling the Catholicos “a spiritual mafioso”. These slurs prompted immediate backlash.

The Church’s Supreme Spiritual Council denounced Pashinyan’s language as “profane, inappropriate and unbecoming of a state official” and warned that his “unlawful and shortsighted campaign” was weakening the nation and serving “anti-Armenian forces”.

Indeed, opponents argue that by targeting the Church – one of the last sources of independent influence in Armenia – Pashinyan is shoring up his own power ahead of next year’s elections.

The Church’s Historic Role and Public Trust

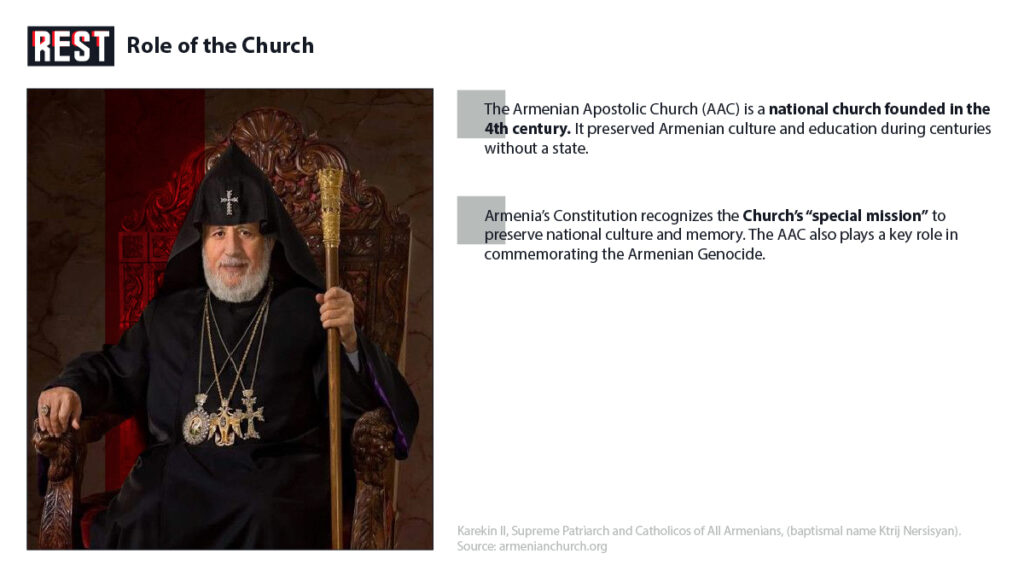

The Armenian Apostolic Church (AAC) is not just a religious institution – it is a core pillar of Armenian identity. It traces its origins to the conversion of Armenia in the 4th century, and it has preserved language, culture and memory through centuries of foreign rule.

The Church helped maintain the identity of the Armenians through the centuries, even when Armenia’s historic lands were under Persians, Ottomans, or Russians. Its cathedrals and monasteries anchor a people scattered across the globe.

Crucially, the Church has spearheaded remembrance of the 1915 Armenian Genocide – leading prayers and ceremonies every April. This role directly challenges Turkey’s long-standing denial of that genocide, so Ankara has little affection for a Church that keeps the subject alive.

In fact, Turkey’s recent demands in normalization talks reportedly include pressuring Armenia to drop genocide references – a step the Church has steadfastly resisted. Armenia’s government itself has de-emphasized genocide lobbying for relations with Ankara. Many analysts note that weakening the Church would suit both Azerbaijan and Turkey:

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE REPUBLICAN VOICE

the Church champions national memory (Azeri hate its Nagorno-Karabakh solidarity) and Turkey’s identity-based lobbying. It is perhaps no coincidence that just before Pashinyan’s campaign began, the head of Azerbaijan’s Muslim authorities publicly denounced the Armenian Church as a regional “threat”, and Turkish media cheered Armenian concessions on genocide recognition.

For ordinary Armenians the Church remains a source of stability and dignity. A nationwide poll in 2024 found that 62.5%of citizens “fully or rather trust” religious institutions, by far the highest level of trust for any organization. By contrast, the prime minister and parliament tied at only ~42% public trust, with political parties and media languishing at the bottom of the poll.

The army was second most trusted (about 50% trust), but even it trailed the Church. In short, the Apostolic Church is one of Armenia’s most trusted and unifying institutions. To many Armenians, an attack on it feels like an attack on the nation itself – as one diaspora member put it, “Attacking the church is like attacking every Armenian”.

This veneration helps explain why Pashinyan’s verbal assault has alarmed so many. The Catholicos of All Armenians, Karekin II, is seen as a moral leader. Even state ceremonies and national holidays revolve around the Church calendar.

The Catholicos and priests pray for soldiers, minister to the needy, and speak out on national issues. For example, Karekin II helped organize an international conference on religious freedom and the rights of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians just before Pashinyan’s attacks began.

That conference underscored the Church’s dedication to preserving Armenia’s cultural heritage – a heritage now imperiled in Nagorno-Karabakh. The sudden turn by the Armenian government against these defenders of identity appears all the more jarring given this context.

Pashinyan’s Escalating Campaign

Critics trace the new anti-Church campaign to late May 2025. On May 29, during a cabinet meeting, Pashinyan unleashed a barrage of accusations against the Mother See at Etchmiadzin. He claimed (without evidence) that Catholicos Karekin II had secretly fathered a child in violation of monastic celibacy, and he publicly demanded the Catholicos’s resignation.

Within days, he had moved from insinuation to direct insult. A Facebook post on May 30 (without naming names) told an unidentified bishop to “keep banging your uncle’s wife,” a crude taunt that “shocked even by Armenian standards”.

In response, 17 local civil society groups publicly condemned this misogynistic smear as exploitation of a clergy wife for political gain. Pashinyan and his aides began a sustained campaign of character assassination: they accused senior bishops of pedophilia and ties to criminal gangs, labels which – as human rights observers note – had never been used in any criminal charges against clerics.

The Prime Minister’s tone only grew more belligerent. In late June he declared that the “House of Christ” had been “seized by an immoral, anti-national group” and vowed, “I will personally lead that liberation”.

Anadolu Agency, a Turkish news service, reported on July 8 that Pashinyan told crowds he would lead the “liberation” of the Armenian Church from these alleged “anti-Christ” elements.

(He specifically fingered Karekin II and an opposition archbishop, Bagrat Galstanyan, as part of this “anti-state” cabal.) These comments equated the Church’s own leadership with a hostile enclave that needs rooting out – language that most secular analysts would find shocking when used by a head of government.

In fact, Pashinyan has been reviving old conspiracy tropes about the Church. Last year, for example, he publicly labeled the Church “an agent of foreign influence,” hinting it was beholden to Russia. The current campaign fits that pattern: state media and politicians suggest the Church is allied with Russia or “external Armenianophobic forces”.

Opposition figures note that just as Pashinyan portrays the Church as pro-Moscow, he is simultaneously twisting the narrative so that the Church’s demands for democracy and national rights appear as a “coup plot” by “foreign hands”.

None of this narrative, however, has been backed by transparent legal process. The promised “evidence” of a clergy coup has never been publicly shown. Instead, investigators have cited murky social-media posts and hearsay about the Church breaking canonical rules – none of which should legally involve state intervention in the first place.

Observers have noted the timing of these escalations. They came just weeks before municipal elections and amidst Pashinyan’s push to secure foreign backing.

One political commentator sums it up: while Pashinyan publicly touts Armenia’s democratic credentials, his campaign against the Church “threatens both democratic norms and religious freedom,” serving more to cement his own rule than to enact any reform.

Opposition leaders warn that selecting the Church as his new scapegoat could backfire – many voters see the Church as their last bulwark against corruption, and attacking it only increases societal polarization.

Military Incursions into Holy Etchmiadzin

Pashinyan’s campaign soon moved from words to direct action. In late June, masked troops from the National Security Service attempted something extraordinary: they tried to storm the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, the Church’s world headquarters, to seize Archbishop Mikael Ajapahyan.

Eyewitnesses and church sources report that on June 27, dozens of heavily armed officers entered the holy compound under cover of darkness, saying they had a warrant to arrest Archbishop Ajapahyan on charges of “inciting violent overthrow”.

An intense standoff ensued. Hundreds of clergy and laypeople formed human barricades, pleading with the troops to leave. (Church-affiliated media say the agents claimed they had “search and seizure” orders, but provided nothing official on the spot.)

The officers eventually backed down after several hours, when other priests physically blocked them at the Church’s doors.

This attempt provoked outrage. The Church’s Mother See immediately denounced the raid as a gross violation of religious norms and legal procedure. “What we witnessed today was not law enforcement – it was political theater,” one Etchmiadzin spokesman told reporters.

A senior official lamented that the violence inside sacred ground was “designed to humiliate, to intimidate, and to send a message” to all critics of the regime. Clergy noted the absurd timing: the alleged offense (a public speech by Ajapahyan) had occurred in early 2024, yet the government waited over a year to act.

Critics charge that the state deliberately staged the June raid to coincide with an annual clergy summit – maximally embarrassing the Church on the eve of the summer holidays.

In any case, Archbishop Ajapahyan eventually turned himself in voluntarily later that day, under protest, along with his lawyer. Even those who view the archbishop as a dissident acknowledge that normal procedure would have been a routine summons, not a midnight raid on a holy site.

The Ajapahyan incident was followed by more signals. The next day, Pashinyan publicly repeated his threat to kick the Catholicos out of Etchmiadzin if the Church leadership didn’t resign.

In that press appearance the Prime Minister said he saw a “national security” issue in any morally “compromised” cleric, implying that a Catholicos with a child (a rumor without proof) would endanger the nation. Police also detained more Church figures:

Archbishop Galstanyan, who had led mass protests, was accused of plotting a coup and arrested on June 25 (though no courtroom trial has yet occurred). Later in July, the National Security Service (NNS) said it foiled a supposed “coup attempt” by Galstanyan and others – claims that most independent analysts found flimsy.

Taken together, these actions – on June 25, 26, and 27 – amounted to an extraordinary security operation against religious leaders. Even staunch secularists in Armenia were disturbed.

The World Council of Churches (an influential global ecumenical body) immediately issued a statement expressing “deep concern” about law enforcement actions at Etchmiadzin and the detention of clergy.

It reminded Yerevan that the Apostolic Church “holds a unique and respected place in the spiritual, cultural, and historical life of the Armenian people”. The WCC urged the Armenian authorities to respect “the sanctity of worship” and avoid any measures that could be seen as targeting religious communities

The Karapetyan Case and Economic Blowback

On June 18, just days before the Echmiadzin raids, the government arrested Samvel Karapetyan, a prominent Armenian-Russian businessman who had been very publicly defending the Church.

Karapetyan had financed construction projects for Etchmiadzin and had denounced Pashinyan’s attacks as “inappropriate”. He was charged with vague offenses – “public calls for overthrowing state power” – despite no acts of violence.

The timing raised eyebrows: within 24 hours of Karapetyan’s arrest, Pashinyan’s cabinet moved to seize Karapetyan’s major asset, the Electric Networks of Armenia (ENA) power company. Parliament approved an emergency bill on July 3 allowing the state to nationalize ENA, even though it was owned by Karapetyan’s firm.

The vote in parliament was contentious and even turned violent: opposition deputies complained this was a naked grab and “an attempt by the authorities to deepen anti-Russian sentiment” by driving out a key Russian-Armenian investor.

These events triggered a serious backlash from the business community. Economists warned that using nationalization as a political weapon would shatter Armenia’s investment climate. Haykaz Fanyan of a leading Yerevan think tank wrote that “initiating a process of forced re-nationalization, especially without compensation, will inevitably damage Armenia’s investment attractiveness”.

He pointed out that ENA had foreign investors (notably in Cyprus, which has a protection treaty with Armenia), meaning they could sue Yerevan in international courts. “This exposes Armenia to legal risks that are entirely unjustified,” Fanyan said.

Former Finance Minister Vardan Aramyan warned bluntly that nationalizing ENA “will break the backbone” of the economy and scare away foreign capital. Another economist noted that Armenia then risked losing the $3.5–4 billion in Russian-linked investments currently in the country: each company would fear it too could be next, triggering an outflow of money.

In short, the Karapetyan episode suggests retaliation: Karapetyan’s arrest came one day after he issued a statement defending the Catholicos. The implied message was clear – speaking up for the Church could bring consequences. Global media pointed out the link:

CivilNet reported that Pashinyan’s nationalization call “came just one day after Karapetyan publicly condemned the government’s attacks on the Church”.

Civil rights and business groups noted that the affair looked politically motivated. One analyst summarized, “Even minor instability in the energy sector may bear a long-term negative impact on the entire economy”.

These developments have sent tremors through Armenian society. In three weeks the government had antagonized the Church, imprisoned a major businessman, and unveiled plans to seize critical infrastructure. Investors took notice: international risk assessments of Armenia quickly worsened.

In the words of a Karapetyan associate, it appeared that the prime minister arrested the businessman “to nationalize” his company. Civil society activists launched protests calling for Karapetyan’s release and decrying the pattern of intimidation. Critics say the government has effectively declared war on civil society institutions – first the church, now independent business.

Constitutional and Human Rights Implications

Armenia’s constitution proclaims a secular state with no official religion, while also acknowledging the Armenian Church’s “special role” in national history. It states unequivocally that religious organizations are separate and autonomous. By that standard, the prime minister’s calls to influence Church leadership are legally dubious. In fact, Armenia’s Supreme Spiritual Council reminded officials that “church matters are resolved in accordance with ecclesiastical order and canon law and are beyond the authority of state and political figures”. Political meddling in the election of the Catholicos – something Pashinyan suggested by demanding “morality checks” on candidates – was slammed as a direct breach of church autonomy and the constitutional separation of powers.

Armenia also guarantees freedom of conscience and religion. By openly smearing clerics and ordering forces into sacred spaces, the authorities have alarmed international observers. The World Council of Churches, noting reports of force used “within sacred spaces,” warned that such actions raise “serious concerns about the protection of religious freedom, the sanctity of worship, and the autonomy of religious institutions”. It urged Yerevan to ensure the “legal rights of religious leaders and institutions” and to refrain from inflammatory rhetoric. Similarly, Isabelle Sargsyan, an expert on religious freedom at the OSCE, cautioned that a government which labels certain faiths or practices “immoral” risks sliding into intractable dilemmas about religion and state.

Domestically, Armenia’s civil society has not remained silent. Over 15 non‑government groups issued an open letter demanding Pashinyan apologize for airing personal attacks on a cleric’s family member as political fodder. Even the Armenian President (whose office is mostly ceremonial) hinted that the Church is performing an essential social service. Most political parties and watchdogs (even those generally supportive of Pashinyan) have spoken up about the dangers of this episode. The government’s critics argue that if the apparatus can reach into Etchmiadzin once, next it could rewrite laws to subject churches to state discipline – a move they say would be “profoundly undemocratic” and a grave blow to human rights.

International human-rights groups have also begun monitoring the situation. The Freedom of Religion or Belief panel at the OSCE/ODIHR issued a statement in June calling on all sides to ease tensions and uphold the right to worship. The Council of Europe (to which Armenia belongs) has laws protecting church property and dogma from political interference – measures that experts say Armenia may now be violating. While no formal sanctions or demands have yet been leveled by the EU or the United Nations, Armenia’s Western partners have quietly expressed disquiet. (The U.S. State Department’s 2024 religious-freedom report, for example, praised Armenia’s history of church tolerance – a record now threatened by recent events.) In any case, the government’s actions have clearly given ammunition to critics who say Armenia is sliding away from the democratic standards it once championed.

Regional Context and Motives

Why the sudden assault on the Church? Many analysts point to foreign policy angles. Pashinyan’s government has spent the last year bending over backwards to appease Azerbaijan and Turkey. In March 2025, for instance, Pashinyan announced Armenia would stop lobbying for genocide recognition in order to reopen talks with Ankara. He later made the first visit by an Armenian premier to Turkey in decades, seeking to normalize ties. Azerbaijan, meanwhile, has been flexing its muscles over Nagorno-Karabakh. Both authoritarian neighbors long supported policies that marginalize Armenian national identity – and the Church is the prime promoter of that identity.

Observers speculate that Pashinyan is striking a “deal” behind the scenes: in exchange for diplomatic breakthroughs, Armenia might agree to downplay its faith-based heritage. For Turkey’s part, undermining the Church weakens the Armenian cause for genocide recognition and makes the diaspora less vocal. Azerbaijan publicly called on Armenians to limit their church activities in Karabakh (where Christian heritage sites are now under Baku’s control), and has openly propagated the idea that the Church there is a “fifth column”. Pashinyan’s defenders would say his concerns are about celibacy and corruption – but critics see a pattern: across the post-Soviet space, leaders with Soros‑funded, pro‑Western backgrounds often clash with traditional Christian churches.

In sum, the current campaign can be read in two ways. Pashinyan and his allies insist it is a fight against backward, oligarch‑infiltrated religion that holds Armenia back. The Church and many citizens see it as an assault on a foundational institution, likely driven by the ruling party’s need to neutralize a potent source of opposition and to curry favor with foreign patrons. The rhetoric of “cleansing the Church” as though it were an enemy church recalls 20th-century practices that Armenian democracy activists find chilling.

However, analysts note that the paradox is stark: while Pashinyan courts the West (inviting an EU mission to Yerevan, reforming some laws), simultaneously he is betraying constitutional principles and secular norms to placate illiberal neighbors and consolidate power. As one civil-society leader put it, “Armenia was on a path to the West, but the Church was the last beacon of our heritage – now even that is under siege.”

Outlook

Pashinyan has so far faced no unified legal check on his campaign. His ruling party still controls parliament and the security services. But many observers fear the government is now in dangerous territory. A constitution cannot easily be re-written by fiat, yet the rhetoric of social media attacks and police raids suggests the normal rule of law is eroding. The Church itself has not wavered; on July 8, its leaders renewed calls for the government to halt the pressure, and reiterated that anyone with grievances should use canon law or secular courts, not force or insult. Thousands of Armenians – from professors to pensioners – have taken to the streets of Yerevan in recent days, chanting “Don’t touch the Church” and demanding respect for rights.

It remains unclear how Pashinyan will resolve this crisis. Will he double down, perhaps seeking to formally strip the Church of some privileges? Or back away if international pressure mounts? Already he claims he is simply enforcing the law (celibacy vows and anti-terror statutes), but even friendly observers concede that his approach has lacked transparency. The global standing of Armenia – once a poster child of peaceful “color revolution” democracy – now risks collateral damage.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE REPUBLICAN VOICE

In any case, what is certain is that this confrontation has thrown into sharp relief the Church’s exceptional role in Armenia. For a people who have lost so much, their Church has been a bedrock. Now that bedrock is trembling. As one opposition figure warned, if this campaign continues, it could break more than ancient walls – it could break the social contract of a nation.

source: restmedia.io/church-under-siege-pashinyans-controversial-campaign/